THE WINDING ENGINES AND ENGINE MEN OF CHATTERLEY WHITFIELD

THE WINDING ENGINES

AND ENGINE MEN

OF CHATTERLEY

WHITFIELD

No greater collection of steam driven

winding engines could be found in the land.

Five shafts, all in a row and all on one site was unusual and formed a

huge deep pit mining colliery. From the

smaller engines of Middle Pit, Winstanley and Platt Pit to the gigantic

monoliths of Hesketh and Institute. They were a magnificent spectacle to see

and hear operating, lowering and drawing coal, men and materials with speed and

efficiency.

The

Royal Navy called them 'grease monkeys' but that job description at Whitfield

was 'oiler and cleaner'. At the age of

15 in 1949 I was just called an 'oil lad' and in my teen years it was my job to

clean, oil and grease those engines under the watchful eye of the winding

engine men (operators). They had cause

to be wary. Shortly before my arrival

one such 'oil lad' had been killed instantly in the crank race at the Middle

Pit. I eventually became a 'winder' at

the minimum age of 22 but I left the industry to pursue another career in

1960. It was during this period, the

fifties, that Whitfield was having its 'heyday' with coal production at its

highest serving the country, which was still struggling after the war years.

The

winders were almost a race apart and were no doubt selected for their sobriety

and trustworthiness before they developed their considerable skill. In some

cases the job ran in families with fathers and even grandfathers having done

the same job. In those days they all

worked a 7 day week in rotating shifts to cover the 24 hours at the 3 coal

drawing pits, Hesketh, Institute and Middle Pit. A spare winder to stand in occasionally would

be available and another would operate the Winstanly engine on a single day

shift. Very often they would work 12

hours between 2 of them to cover a colleague off with illness.

The

winders I knew were all dedicated individuals but were often 'crusty' and would

not suffer fools gladly. As an 'oil lad'

I more than once felt the brunt of their wrath if my work was perceived to be

below par. These men were responsible

for the engine houses and the engines within, showcases of cleanliness and

smooth running. They were justly and sometimes obsessively proud of their

engines.

Coal

owners and later during my time, the National Coal Board managers, would often

proudly bring VIP visitors to see the engines and were usually amazed at the

spectacle. It was said 'you could eat

your dinner off the engines'.

The

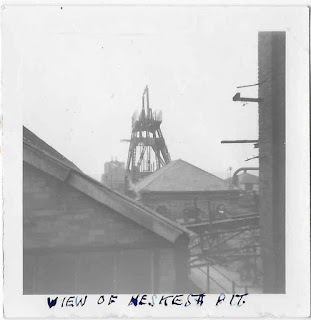

Hesketh engine was undoubtedly the top of the bill as a show-piece and it is of

great sadness that it is in a rusty, parlous state at this time (2017). However, it is still intact and hopefully it

may be restored sometime in the future.

The forty or more years it has been out of use has taken its toll. The sheer size and dimensions are

considerable when compared to the diameter of the car combustion cylinder which

is 2 to 3 inches in diameter with a 5 inch stroke whereas the Hesketh's 2 cylinders have an internal diameter of 36

inches and a stroke of 6 feet! The drum,

like a bobbin onto which the winding ropes (steel cables) were wound and

unwound is a semi-conical shape. This

allowed the smaller diameter part of the drum to work like a lower gear for the

rope, drawing its load out of the bottom of the deep shaft and gradually easing

and speeding up as it rose and gained momentum.

The

Institute engine was no less remarkable if not quite having the allure of the

more modern Hesketh engine. In fact, the

basic dimensions were the same but of a simpler and older design, being

installed in the 19th century and of a marine type sometimes used in

early steam ships. It was nicknamed the

'the Cockshead' because of the beak like pointed structure at the top of the

headgear. This was amazingly, a vertical

engine, unlike all the others at Whitfield which were horizontal. It was housed in five floors, two of which

were below ground level. The drum,

weighing 50 tons, was a simple parallel shape, like a bobbin and was suspended

on the top floor of the building. It was

a powerful experience to stand near the engine man on the ground floor,

watching and almost feeling the hot piston rods working the upward cranks to

the hissing and puffing of super heated steam. The supporting walls were

immense but nevertheless the building shuddered during the operation of the engine. The engine and engine house

were no less clean and spotless than the Hesketh with similar tiled floors to

be mopped and cleaned to kitchen standard.

The

oil lad was nearly always out of sight of the winder at the Institute and

oiling and greasing took place during the momentary pauses at the end of each

run (top to bottom with the cages and vice versa). The winder had to rely on

shouted signals from the lad on other floors to safely start the next run. What 'Health and Safety' would make of this

nowadays is something to ponder.

Sadly

the Institute was demolished and removed.

A great loss to history.

The

Middle Pit, along with the Hesketh and Institute, was also coal drawing. It was a shallower shaft and the engine was

smaller but it had 3 decker cages and was extremely busy, swiftly lifting a

seemingly never ending stream of laden coal tubs.

Like

the other two coal drawing pits, the night shift was always a busy time with

constant ongoing maintenance of the shaft and equipment and during the night

the winder himself would, during quiet times, clean various parts of the engine

that could not be accessed during daytime operations

This

engine has been demolished and removed.

The

Winstanley Pit had the smallest winding engine.

It was not used for coal drawing but was near to and secondary to the

Middle Pit and at the same depth. It was

of course mandatory to have at least 2 shafts to each mine. This had enclosed headgear with an airlock

system of doors. Fresh air was drawn

down the open Middle Pit out through a vent near the top of the closed

Winstanly Shaft by the use of a steam driven fan engine.

It

should be said here that a similar air flow system was operated with the other

3 shafts. The Hesketh being open and the

Institute and Platt Pits both being enclosed and air locked. A powerful small steam engine in a separate

building drew the air through this deep mine complex. Such was the importance

of maintaining a clean air flow that there was a separate engine (unused) in

another building near the Platt Pit in case of a failure or major maintenance

to the main fan engine.

It

was of course a legal requirement that all coal mines should have at least 2

shafts. It was equally important to have

an air flow system and a secondary means of escape from below.

Historically

these changes were embraced legally following a major disaster in 1862 at

Hartley colliery near Newcastle upon Tyne.

Almost unbelievably this deep mine had only one shaft which was divided

throughout its depth by a wooden shuttering construction which allowed one side

to be used for lowering and lifting men, materials and coal while the other

side contained vertical pipes which pumped water out of the workings below. All mines would fill with water if not pumped

out. The pump was operated by a huge

beam engine. The heavy cast iron beam, which worked in an up and down motion

over the shaft, broke off and plunged down the shaft taking with it all the

dividing woodwork and crushing it down to about a 3rd of the shaft

depth where it stopped in a tangled mess, blocking the shaft. All 204 men and boys working below perished

before a rescue could be made. The

youngest was 10 and the oldest 71. It is

hard to believe that some callous coal owners needed the law to ensure they had

two shafts. The life of a coal miner in

those days must have been regarded as cheap.

Even

in my day coal mining was a hazardous business and many was the time that I saw

injured men (sometimes fatally) brought out of the pit on stretchers.

Lastly,

the Platt Pit is probably the most intact at this time and as I mentioned

before it had enclosed and air-locked headgear. To this day its distinctive

green painted enclosure panels are visible.

It shared common airways with the Hesketh and Institute.

The

engine was much smaller than the Hesketh and Institute engines but larger than

the Middle Pit and Winstanly engines. It

was occasionally used for materials but was mainly for safety in the fifties.

Finally

I should mention some of the personalities involved with winding engines at

that time. As I mentioned previously,

some of the winders ran through

families. My father Eddie

Sherratt was a winder at the Institute and later at the Hesketh. His father was a winder at the Institute and

so was his grandfather. The latter was

nicknamed 'Peg-leg' due to his loss of a

leg in a dreadful accident when a cage he was entering at the pit bottom

rose before he was fully inside,

destroying his leg.

The

Simpsons were another such family.

Father and then son (Ted) operated the Middle Pit engine, the latter during part of the time I was there as

an 'oil lad'. Another greatly experienced winder there was Cecil Johnson, a

dignified and kindly man who operated with great skill. Another father and son were Fred and his son

Alf Rhodes who operated the Hesketh and Middle Pit engines respectively.

Among

the larger than life personalities were Tom Boulton (Hesketh) and Harry

Holdcroft (Institute). Tom Boulton's

brother, Syd, was not a winder but is

worthy of mention as not only was he a very efficient engineer, he

specialised in hydraulics and took part in promoting Whitfield's museum after

its closure as a working colliery. He

was an ex submariner.

Claude

Winter was another highly talented engineer who specialised in reshaping the

white metal bearings in the engines, a major undertaking when the drum and

spindle shaft had to be raised out of the bearing beds. There are many others

worthy of mention and to their memories I apologise.

Personally

I am not sorry to see the end of deep coal mining which has always been dusty

and dangerous, although many would disagree.

Ray Sherratt. QPM

Comments

Post a Comment